Return on Investment of Public Health Interventions a Systematic Review

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

The social value of investing in public health across the life course: a systematic scoping review

BMC Public Health volume xx, Article number:597 (2020) Cite this commodity

Abstruse

Background

Making the instance for investing in public health by illustrating the social, economic and environmental value of public health interventions is imperative. Economic methodologies to help capture the social value of public health interventions such as Social Return on Investment (SROI) and Social Cost-Benefit Assay (SCBA) accept been developed over past decades. The life course arroyo in public health reinforces the importance of investment to ensure a good first in life to safeguarding a safe, healthy and active older age. This novel review maps an overview of the application of SROI and SCBA in the existing literature to identify the social value of public health interventions at private stages of the life grade.

Methods

A systematic scoping review was conducted on peer-reviewed and greyness literature to identify SROI and SCBA studies of public health interventions published between January 1996 and June 2019. All chief enquiry articles published in the English language language from high-income countries that presented SROI and SCBA outputs were included. Studies were mapped into stages of the life class, and information on the characteristics of the studies were extracted to help understand the awarding of social value methodology to assess the value of public health interventions.

Results

Overall twoscore SROI studies were included in the final data extraction, of which 37 were published in the grey literature. No SCBA studies were identified in the search. Evidence was detected at each phase of the life class which included; the birth, neonatal period, postnatal period and infancy (due north = two); childhood and boyhood (n = 17); machismo (primary employment and reproductive years) (north = viii); and older machismo (north = 6). In addition, 7 studies were identified equally cantankerous-cutting across the life grade in their aims.

Conclusion

This review contributes to the growing prove base of operations that demonstrates the employ of social value methodologies within the field of public health. By mapping evidence across stages of the life class, this written report tin be used as a starting point past public wellness professionals and institutions to take forward current thinking nearly moving abroad from traditional economic measures, to capturing social value when investing in interventions across the life course.

Background

The demand for investment in health and well-existence is stronger than ever in the face up of multiple challenges and adversities [1]. This is becoming of item importance every bit countries are moving abroad from traditional methods of measuring success (for example, analysing Gross Domestic Product (GDP)) towards measuring wider economic and social value created. For example, in 2019, the New Zealand Government introduced a 'wellbeing budget' and have broadened their definition of success to comprise not but the wellness of their finances, only also of their natural resource, people and communities [2]. Making the instance for investing in public wellness by collectively illustrating the social, economical and environmental value of public health interventions is imperative to enabling sustainable and fair policy and action for the do good of people, communities and societies.

Historically, traditional 'value for money' approaches such as cost-effectiveness and cost-utility have been the overriding gene which has determined all public sector procurement decisions, taking into business relationship only the monetarised costs of productivity and outputs of an intervention. This is underpinned by a broad evidence base illustrating the render on investment in economical terms and value for money of investing in public health interventions across the life course [i, 3, 4]. However, due to the potential added value of public health interventions (social and environmental, as well as physical) on an individual'due south health and well-existence, it is becoming increasingly important to capture the wider social value of interventions, services and policies [5, six].

Social value is defined as the quantification of the relative importance that people place on the changes they experience in their lives [7] accounting for the broader human being and societal factors that consequence from an intervention. For example, the value individuals experience from increasing their conviction, or from living next to a park in a community. Investing in something which creates social value goes beyond the fiscal value of the service existence delivered, to include potential benefits to the local and national economic system, the individuals involved, their families and communities.

Past moving away from traditional measures of capturing fiscal value, social value measurements present the full holistic range of outcomes, which is imperative to establishing bear on and providing an enhanced agreement of reality [3]. Internationally, there is a body of bear witness which uses wellness economic measurement techniques that capture the social value of investing in public health [1, 8,9,10]. For example, the bear upon on inequalities, local employment, health and well-beingness, community development, social capital and ecology sustainability. Social Toll-Benefit Analysis (SCBA) and Social Return on Investment (SROI) are the predominant tools used to assess the wider value of services or interventions past identifying and evaluating 'soft' outcomes, which have traditionally been difficult to measure [8]. SCBA places a monetary value on predetermined outcomes not conventionally measured by other economic methods, such every bit the well-beingness of individuals and wider stakeholders such as family or the community. SROI takes this some other pace further and consists of a framework for measuring a much broader concept of value past measuring alter that matters to stakeholders, including a consideration of the economic, social and environmental impacts of investments [11]. Carried out either retrospectively (evaluative) or prospectively (forecast), SROI tin help organisations move away from purely financial accounting towards a more comprehensive accountability of value created through an inclusive process of stakeholder engagement and involvement [3, 11].

A vast body of prove illustrates that key stages across people's lives accept item significance to their wellness and well-being, which is reflected through the life course arroyo in public wellness [12,13,14]. A life course approach suggests that an individual's health, a population's chronic disease epidemiology and wellness equity is dependent on the interaction of multiple risk factors, all apparent at unlike phases beyond people's lives [1, 14,15,16]. Across an individual's life, biological, social and environmental influences can accumulate and have positive and negative effects on the weather condition for mental and physical health [13]. Examples are the associations betwixt family influence and childhood obesity, or the socioeconomic characteristics of the female parent's state of nativity and psychotropic medication in Swedish adolescents [14, 17]. The life course approach reinforces the importance of potent investment from ensuring a good start in life to safeguarding a safe, healthy and agile older age. By addressing not just the consequences of sick wellness, but considering the causes and contributors, the life class approach promotes timely investments which produce a high rate of return for both the health of the public, simply also financial benefits to the economy [xviii].

The life course tin can be split into the following key stages: 1) birth, neonatal catamenia and infancy; ii) early and later childhood and adolescence; three) adulthood (main employment and reproductive early years); and 4) older adulthood [19]. By investing at each stage, evidence suggests societal and economical benefits tin can exist achieved, every bit well as improvements in wellness at the individual level [12]. The case for investment in the early years has been evidenced through international research [3], and promoted through high profile reports, such as the Marmot Review [13] and the World Wellness Organization'southward Commission on Social Determinants of Health [20]. Giving every child the best start in life is crucial to reducing health inequalities and inequity. The early childhood period is considered to be the most important developmental stage throughout the life course [21], and harmful childhood experiences are linked to long-lasting disadvantage and ill health, with substantive costs to the private and the economic system [22]. For example, it has been estimated that investing in breastfeeding has a clear positive return on investment across the life course [23]. In add-on, poor education tin can be detrimental to wellness and life prospects [24, 25], with prove suggesting that investing in early education can result in high social and economical returns, and likewise has positive intergenerational effects [i]. Later childhood, developed life involves maintaining the highest possible level of office. The rate of decline at this stage is largely determined by behavioural lifestyle factors adopted at this phase, or previously, such every bit smoking, alcohol consumption, levels of physical activeness and diet. Finally, the importance of investing in wellness in older life is focussed on preventing disability and maintaining independence [26].

Previous secondary enquiry has been undertaken to collate existing testify on the SROI of public health interventions [three, nine, x]. The review outlined in this paper aims to build on these findings to map out the existing SROI and SCBA evidence on the social value of public wellness interventions across stages of the life form. Past exploring the extent of the literature, this review will identify the characteristics of SROI and SCBA show of public health interventions, illustrate how testify is distributed across stages of the life class, outline the range of SROI values presented in this evidence, and propose what gaps exist in the current show base of operations at the different life form stages.

Methods

To gain an overarching understanding of the available evidence on the social value of public health interventions across the life class, a systematic scoping review was undertaken, using a comprehensive search strategy and selection criteria. A scoping review is defined as a preliminary assessment of the potential size and scope of the available research literature, which aims to identify the nature and extent of research show on a topic. Evidence suggests that used appropriately, this method tin utilise a comprehensive and systematic approach to mapping the literature, fundamental concepts, theories, testify and enquiry gaps in a field using broadly framed questions [27].

Search strategy

Show was collated from peer-reviewed academic research and grey literature. The search terms used were "public wellness" OR "health promotion" OR "main prevention" OR "life course" OR "health" and "interven*" or "program*" and "social return on investment" OR "social toll benefit analysis". These search terms were used to search on championship or abstract within peer-reviewed databases (PubMed and ProQuest). The grayness literature was explored using the same search terms as the bookish search on Google Scholar and organisational websites (World Health Organization, public health institutional websites, Social Value United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and the New Economic Foundation). Manual snowball and forrad commendation searches were also conducted on the academic and grayness literature identified for inclusion. One researcher independently conducted the search in July 2019. An additional researcher also screened the testify, and whatever conflicts in stance were discussed by the two researchers and a consensus agreed upon.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

At the initial search phase, publications were included if they were written in the English language linguistic communication and published from January 1996, as this was when the first social value report using SROI was published, to June 2019. At the screening stage, publications were but included if they focussed specifically on SCBA, SROI or social value of public health interventions, and included the SROI output of primary studies from high-income countries to farther limit the studies included. Finally, at the eligibility stage, articles were excluded if they were solely protocol papers and included no data or description of the economic, social or ecology returns of a public health intervention.

Data extraction and synthesis

For the purpose of this study, all evidence captured was categorised into the stages of the life course; nativity, neonatal period, post-natal period and infancy, childhood and boyhood, adulthood (main employment and reproductive years), and older adulthood. Family interventions targeted at developing the health and well-beingness of children were included in the 'Childhood and boyhood' category, as the primary aims were to provide support for the children. An additional category of 'Cross-cutting' was also included to capture those interventions targeted at populations which cut across several stages of the life grade.

A summary tabular array was used to capture necessary information about each individual study. This included year and country of publication, social value methodology used, who deputed the study, public wellness topic the intervention was focussed on, target population of the intervention being assessed, details of stakeholder appointment, how outcomes were measured, economic results including the crude SROI ratio for the fourth dimension horizons included in the written report, type of publication (bookish or greyness literature) and limitations of the written report identified by the authors. In addition, to assess the quality of the identified studies, a quality assessment framework based on a 0–12 point scoring alphabetize [28] as used in similar studies [nine], was used to score the bear witness which contributed to the understanding of the use of SROI and SCBA methodology. This framework assesses the quality of studies based on the following criteria: transparency about why SROI was chosen; documentation of the analysis; study design including approximation of counterfactual; precision of the analysis; and reflection of the results.

The information extracted was used to develop a literature map that helped to illustrate the distribution of the testify of the social value of investing in public health beyond the stages of the life course. Public health topics, target populations, aims of intervention and the crude SROI ratios were summarised for each stage of the life course. Finally, the summaries presented were used to propose gaps in the existing evidence base.

Results

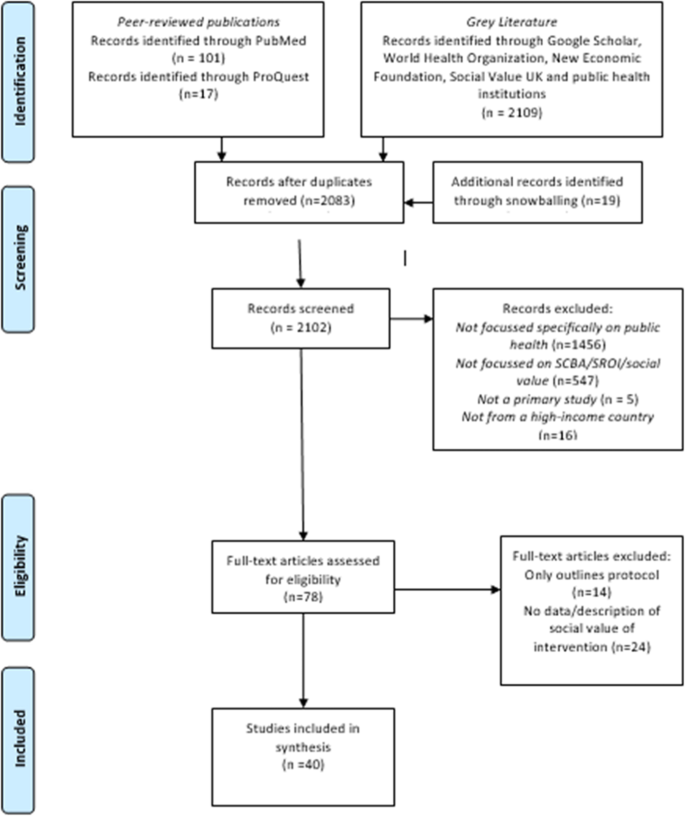

To report the findings of this scoping review, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) approach was followed [29]; Fig. ane]. Following a systematic arroyo, a total of 40 studies were identified for inclusion in the final evidence synthesis.

PRISMA flowchart

Written report characteristics

Of the 40 included studies, but three were published in the academic literature with the remaining 37 published in the grey literature. With regards to country of origin for the studies, 87.5% (n = 35) had been carried out in Britain, with the remaining 12.5% (n = five) originating from Republic of ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the Netherlands. Although the search strategy used in this study included SCBA studies, only SROI studies were identified in the literature. Of these, 7 were categorised equally prospective or forecast SROI studies (i.e. predicted the bear upon of a project or activity), with the remainder beingness evaluative or retrospective SROIs (i.e. measures the modify a project of activeness has delivered). The testify identified through this review indicates that the number of SROI studies peaked in 2012 and 2013, with a steady reject towards 2019 (Table 1).

With regards to the quality of the final included evidence, quality scores for individual studies ranged from 4 to eleven (mean = eight.45). Using the criterion of a score of seven or higher up to indicate loftier quality [28], 36 studies (ninety%) were considered to exist of a loftier quality with iv considered to be of a lower quality using the data within the publications (Table ane). No report achieved a maximum score of 12 which reflects findings elsewhere [xix] and is because none of the SROI analyses identified in this review had a control group inside their SROI designs, which is an element inside the scoring index of the quality assessment framework used in this review [28].

Distribution of social value evidence across stages of the life course

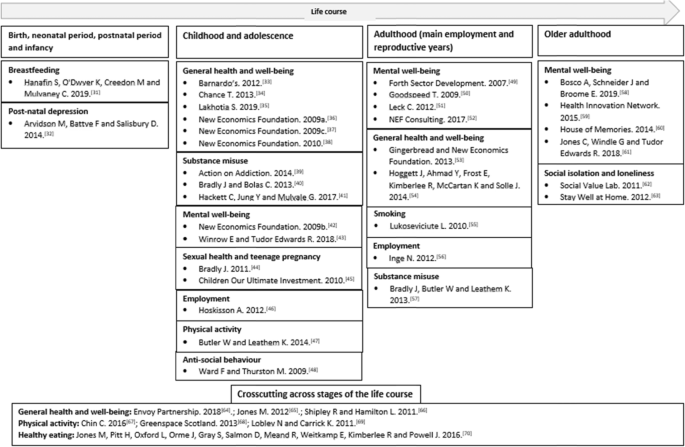

The literature map (Fig. 2) illustrates the evidence included in this scoping review, according to life course phase and public health topic. Within the first stage of the life course, which we classified equally 'birth, neonatal catamenia, postnatal period and infancy', ii studies were identified. A total of 16 studies were identified at the next stage of the life course categorised equally 'Childhood and adolescence', followed by 9 studies at the 'Adulthood (main employment and reproductive years) stage. Finally, 6 studies were categorised into the 'Older adulthood' stage. In addition, there were seven studies which were included into the supplementary category of 'Crosscutting' as these interventions were targeted at a range of individuals at differing stages of the life course, for example an intervention which developed volunteer Community Champions to promote health and well-existence to all residents in a local community in England [30].

Literature Map: Evidence for Social Return on Investment (SROI) across stages of the life form

Nascence, neonatal catamenia, postnatal menstruum and infancy

Of the two studies identified in the first stage of the life course, one focussed on the topic of breastfeeding with female parent [31] reporting a crude SROI of €15.85 per €1 invested, whilst the other outlined the SROI of an intervention to support those affected past mail-natal depression [32] showing a rough SROI of £vi.50 per £1 invested [Tabular array 2].

Childhood and adolescence

In total, 16 SROI studies were identified in the babyhood and adolescence phase of the life course (Table three). These focussed on a range of public health topics which included the following: full general health and well-being [33,34,35,36,37,38], substance misuse [39,40,41], mental well-existence [42, 43], sexual health and teenage pregnancy [44, 45],, employment [46], concrete activity [47] and anti-social behaviour [48]. SROI ratios for interventions at this stage of the life course ranged from £2 per £1 invested [33], to £9.xx per £1 invested [37].

Adulthood (main employment and reproductive years)

Of the nine studies identified within the adulthood stage of the life grade, four focussed on interventions that aimed to improve mental well-beingness [49,l,51,52], ii on general wellness and well-being interventions [53, 54], i on smoking [55] one on employment [56] and 1 on substance misuse [57] (Table 4). The SROI ratios ranged from £0.66 per £one invested reported for an intervention seeking new means of working with troubled families by changing trajectories for families and changing the ways services are delivered to them [54], to £7 per £ane invested for an intervention that focussed on providing support for adults with multiple long-term wellness conditions, low-level emotional health concerns or lifestyle or social issues [52].

Older adulthood

The six studies identified in this review within the life grade stage of older adulthood focussed on two main public health topics; mental well-existence [58,59,sixty,61] and social isolation and loneliness [62, 63] (Tabular array 5). The SROI ratios ranged from £11 per £1 [63] to £1.20 per £i invested [58].

Cross-cutting across the life course

7 SROI studies were classified as aiming to cut across dissimilar stages of the life class, with three aimed at promoting general health and well-being [30, 64, 65], three focussing on interventions that aimed to improve physical activity [66,67,68], and i focussed on salubrious eating [69] (Table six). For interventions that cut across the life course, SROI ratios ranged from £44.56 per £ane invested and £2.56 per £one invested.

Discussion

This review contributes to the growing prove base that demonstrates the use of social value methodology inside the field of public wellness [nine, 10]. It is acknowledged there may be wider existing economical evidence of wider policy interventions assessing potential health benefits, for example of transport and housing policy, still this search focussed on public wellness interventions direct targeted at improving health. Complementing previous reviews that have aimed to capture the existing evidence on the utilise of SROI methodology on public health interventions and services [9, 10], this review takes a unique approach to mapping studies from both the academic and grey literature across stages of the life course. Results can exist used every bit a starting point by public health professionals and institutions to develop an agreement of the social value of public health interventions beyond unlike stages of the life course, which could be used to inform policy, practice and investment decisions.

This review identified that the majority of SROI studies on public health interventions have been carried out in the United Kingdom. This may be a reflection of the introduction of the Public Services (Social Value) Human activity 2012 [seventy] and the growing emphasis to undertake affect assessments, particularly inside the private and third sector [71]. Captured testify was mostly evaluative in nature, with the reporting of SROIs peaking in the years of 2012 and 2013, illustrating a steady decline towards 2019. This is interesting to note, due to the growing interest in recent years of moving away from traditional economic measures of success within economies, towards a wellbeing approach and new measures of capturing progress [2, 72]. Sparse literature was identified within the bookish evidence base with the majority beingness published in the grey literature. This again aligns with existing reviews, which notation this may exist a result of weaknesses in SROI methodology which potentially stifle opportunity for academic publication [nine–10; 74]. Another reason for this may be associated with the type of organisations undertaking SROIs, for case not-for-turn a profit and charitable organisations, who may not traditionally focus on academically publishing their piece of work [73]. In addition, although this written report sets out to capture both SROI and SCBA evidence, no SCBA studies were constitute to focus on public health interventions. These results suggest that SCBA is non yet a recognised methodology used to capture the social value of public wellness interventions and may require further investigation and promotion. In addition, these results suggest that researchers have found the social value methodologies discussed in this newspaper potentially hard to conform to their scenarios, or hard and labour intensive to undertake.

With regards to the expanse of public health, it is interesting to note that no evidence was identified that captured the social value of public health interventions outside of the field of health promotion. For example, screening services, vaccination or environmental wellness initiatives. The reason for this again may be related to the type of organisations currently utilising SROI to undertake economical evaluations, for example tertiary sector organisations as opposed to national public health institutes. Another reason would exist the preference of using more than 'established' wellness economics methods, such as price-effectiveness or cost-benefit analysis, due to availability of 'hard' clinical outcomes, such every bit reduction in mortality, morbidity and hospital admissions. However, these traditional methods neglect to capture the 'soft' outcomes, related to additional benefits (added value) to the individuals, their families, carers, communities, social, concrete and economic environment.

The life course perspective in public health emphasises the important role and variability of social, environmental and economic factors play in the development of dissimilar health trajectories across the life stages [74]. Inside this review, nosotros mapped the evidence of the social value of public health interventions beyond the life course. The childhood and adolescence stage comprised near half of the studies identified (n = 17), with most focussing on general health and well-beingness and substance misuse. Just 2 studies were found to be reported in the birth, neonatal period, postnatal menstruation and infancy. The small number of studies identified in this first stage of the life course could be due to the methodological challenges in SROI of capturing the value of the long-term outcomes. This is referred to as 'deadweight' in SROI methodology, or what would have happened anyway, which is more complex to measure and forecast across the life course [75]. In improver, there are complexities with measuring 'well-becoming', which focusses on the future, equally opposed to 'well-being' which focusses on the present [76], particularly if trying to capture the value of an intervention across the whole life grade. The remaining evidence was split relatively equally over the remaining stages of the life course, cutting across the topics areas of mental well-beingness, social isolation, general wellness and well-being, substance misuse and good for you eating. As with previous research, all SROI testify reported encouraging SROI ratios, indicating that the interventions identified at each stage of the life grade produced a positive overall social value [nine]. These examples can exist used every bit a starting point by stakeholders to help guide further work into estimating the social value of public wellness interventions at different stages of the life course, depending on the public health surface area or topic. This would potentially help identify the interventions with highest or higher value for each life stage or across all stages; or which public health areas would be nigh relevant, for instance bring the nigh value, to invest in within each life stage.

Limitations

Although the methodology used for this review was appropriate for the aims of the research, there are limitations, which are important to note. The search terms used in our systematic scoping review may not accept captured every piece of prove on the social value of public wellness services and interventions, in particular those public health interventions which may be referred to by some other title. An instance of this is community engagement interventions, which could potentially have an impact on the wellness of the public across particular stages of the life course and create social value. This was coupled with the difficulty of searching for social value studies in the grayness literature where no dedicated database exists internationally [9].

Equally function of a credible methodological process [11], the majority of studies in this review carried out sensitivity analyses on their SROIs based on different scenarios and assumptions. It was across the telescopic of this study to interpret the crude SROI values reported and their associated sensitivity analyses. In add-on, this newspaper did not aim to compare interventions or stages of the life course to place which create the well-nigh social value. The SROI ratios created past undertaking the standardised methodology incorporates elements which make the finish ratio unique to the intervention being assessed, for example using differing time horizons and subjectivity effectually the proxy valuation process within SROI [77]. Also, what is important to measure out and how is it valued may differ co-ordinate to life phase [76]. In order to compare these values, additional work would be required to business relationship for the caveats around the possibilities of making these comparisons.

Recommendations for further enquiry

At that place is telescopic for farther research to be undertaken which could build on elements outside of the aims and objectives of this study. This review is the first footstep to capturing and mapping the social value of public health interventions at unlike stages of the life course. Farther enquiry is needed to sympathize where social value methodology is all-time suited in relation to measuring value of interventions at the different life stages. There is a articulate need for farther high-quality SROI and SCBA studies to be undertaken and academically published, peculiarly focussing on capturing the social value of services outside of the field of health promotion [10]. In addition, although there is initial inquiry which explores how public health organizations measure value [78], farther exploratory work is also required to encompass how social value is being captured at an institutional level to help build the evidence base and inform the efficient allotment of resource beyond the life course.

Conclusion

There is a significant interest in measuring and capturing the social value of public health interventions to assist guide investment decisions and assist the efficient resource allotment of resources. This paper builds on existing research to understand the existing bear witness base, taking a unique approach to mapping identified SROI and SCBA evidence beyond stages of the life class. From the early years of childhood to older adulthood, the importance of capturing social value has been highlighted, with existing SROI research indicating the positive value of investing in public health interventions. This enquiry has indicated that although attempts have been made to measure out the social value in public health, farther research is needed to develop this field. This includes publishing more case studies within the academic literature, and understanding in more detail how SROI tin can be used to capture long-term outcomes across all stages of the life course. Additional benefit could exist found past further exploring the reasons why some researchers are not utilizing these methodologies and publishing results academically to assist develop the evidence base of operations. Results highlighted within this work tin be used as a starting point by public health professionals, institutions and across sectors to take forward current thinking almost moving abroad from traditional economic measures, towards because the wider determinants of wellness and well-being in their valuations, and to capture and quantify the social value resulting from a wider range of policy initiatives.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this commodity as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

-

Dyakova M, Hamelmann C, Bellis MA, Besnier East, Grey CNB, Ashton K, Schwappach A and Clar C. 2017. Investment for health and well-beingness: a review of the social return on investment from public wellness policies to back up implementing the Sustainable Development Goals by building on Health 2020. Wellness Prove Network synthesis report 51. [Online]. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/investment-for-health-and-well-being-a-review-of-the-social-return-on-investment-from-public-health-policies-to-support-implementing-the-sustainable-development-goals-by-building-on-health-2020-2017 [Accessed 13th November, 2019].

-

New Zealand Treasury. 2019. The Wellbeing Budget. [Online]. Available at: https://treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-05/b19-wellbeing-budget.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Tudor-Edwards R, Bryning L and Lloyd-Williams H. 2016. Transforming Young Lives across Wales: the Economic Argument for Investing in the Early Years. [Online]. Available at: https://cheme.bangor.air conditioning.uk/documents/transforming-young-lives/CHEME%20transforming%20Young%20Lives%20Full%20Report%20Eng%20WEB%202.pdf [Accessed 13thursday Nov, 2019].

-

Masters R, Anwar E, Collins B, Cookson R, Capewell Due south. Return on investment of public health interventions: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Wellness. 2017;71(8):827–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-208141.

-

Shiell A, Hawe P, Aureate Fifty. Complex interventions or circuitous systems? Implications for health economics evaluation. BMJ. 2008;336(1281). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39569.510521.AD.

-

Baker C, Courtney P. Conceptualising the societal value of health and wellbeing and developing indicators for assessment. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25:suppl_3. https://doi.org/x.1093/eurpub/ckv175.048.

-

Social Value United kingdom. 2019. What is Social Value? [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/what-is-social-value/ [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

New Economics Foundation. 2013. Economics in policy-making 4. Social CBA and SROI. [Online]. Available at: https://world wide web.nefconsulting.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Briefing-on-SROI-and-CBA.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Banke-Thomas AO, Madaj B, Charles A, van den Broek N. Social Render on Investment (SROI) methodology to account for value for money of public wellness interventions: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(582). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1935-7.

-

Hutchinson CL, Berndt A, Forsythe D, Gilbert-Hunt S, George S, Ratcliffe J. Valuing the bear on of health and social care programs using social return on investment analysis: how have academics advanced the methodology? A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019:9–e029789. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029789.

-

The SROI Network. 2012. A guide to Social Return on Investment. [Online]. Bachelor at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/The%20Guide%20to%20Social%20Return%20on%20Investment%202015.pdf [Accessed 13thursday Nov, 2019].

-

Jacob CM, Baird J, Barker M, Cooper C and Hanson Thousand. 2017. The importance of a life-course approach to health: Chronic affliction risk from preconception through adolescence and machismo. [Online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/life-course/publications/importance-of-life-course-approach-to-health/en/ [Accessed xviiith Nov, 2019].

-

Marmot Grand. 2010. Fair Guild. Healthy Lives. A Strategic Review of Inequalities in England. [Online]. Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/marmot-review-report-fair-society-healthy-lives [Accessed 13th November, 2019].

-

Pratt BA and Frost LJ. 2017. The life grade approach to wellness: a rapid review of the literature. White paper. [Online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/life-course/publications/life-course-arroyo-literature-review.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed xiiith Nov, 2019].

-

Braveman P. What is wellness disinterestedness: and how does a life-form arroyo take u.s. further toward it? Matern Kid Health J. 2014;18(two):366–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1226-9.

-

Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life class approach to chronic affliction epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(ii):285–93.

-

Van Leeuwen West, Nilsson Due south, Merlo J. Mother's country of nascence and prescription of psychotropic medication in Swedish adolescents: a life class arroyo. BMJ Open up. 2012;2(5):e001260. https://doi.org/ten.1136/bmjopen-2012-001260.

-

World Wellness Organization. 2019. Life-course approach. [Online]. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Life-stages [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Kuruvilla S, Sadana R, Villar Montesinos East, Beard J, Franz Vasdeki J, Araujo de Carvalho I, Bosco Thomas R, Brunne Drisse M-North, Daelmans B, Goodman T, Koller T, Officer A, Vogel J, Valentine Northward, Wootton Eastward, Banerjee A, Magar V, Neira G, Okwo Bele JM, Worning AM, Bustreo F. A life-form arroyo to health: synergy with sustainable development goals. Balderdash Globe Wellness Organ. 2018;96(1):42–50. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.198358.

-

Heckman JJ. 2012. Invest in early on childhood development: Reduce deficits, strengthen the economy. [Online]. Available at: https://heckmanequation.org/resource/invest-in-early-childhood-development-reduce-deficits-strengthen-the-economic system/ [Accessed xiiith Nov, 2019].

-

Commission on Social Determinants of Wellness. 2019. Endmost the gap in a generation. Health disinterestedness through action on the social determinants of health. Final Study of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. [Online]. Bachelor at: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/ [Accessed xiiith Nov 2019].

-

Heckman JJ. Schools, skills, and synapses. Econ Inq. 2008;46(3):289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2008.00163.x.

-

Bellis MA, Hughes 1000, Ford K, Ramos Rodriguez G, Sethi D, Passmore J. Life course wellness consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and Due north America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(x):PE517–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(xix)30145-eight.

-

Renfrew MJ, Pokhrel Southward, Quigley Grand, McCormick F, Play a joke on-Rushby J, Dodds R and Williams A. 2012. Preventing disease and saving resources: the potential contribution of increasing breastfeeding rates in the Britain. [Online]. Available at: https://world wide web.unicef.org.britain/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2012/eleven/Preventing_disease_saving_resources.pdf. [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Marmot Thousand, Allen J, Bell R, Bloomer E, Goldblatt P. WHO European review of social determinants of wellness and the health separate. Lancet. 2012;380:1011–29. https://doi.org/x.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8.

-

Globe Health Organization. 2000. The implications of preparation of embracing. A life course arroyo to health [Online]. Available at: https://world wide web.who.int/ageing/publications/lifecourse/alc_lifecourse_training_en.pdf [Accessed xiiith November, 2019].

-

Grant MJ, Berth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14711842.2009.00848.x.

-

Krlev G, Munscher R and Mulbert K. 2013. Social return on investment (SROI): Country-of-the-art and perspectives: a meta-assay of practice in social return on investment studies published 2000-2012. [Online]. Available at: https://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/volltextserver/18758/ [Accessed 18th Nov, 2019].

-

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke 1000, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, PRISMA-P Grouping. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-assay protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(one).

-

Envoy Partnership. 2018. Community Champions. Social return on investment evaluation. [Online]. Available at: https://www.centrallondonccg.nhs.uk/media/92475/Community-Champions-SROI-2018.pdf [Accessed 13th November, 2019].

-

Hanafin S, O'Dwyer Chiliad, Creedon Chiliad and Mulvaney Clune C. 2018. Social render on investment: PHN-facilitated breastfeeding groups in Republic of ireland. [Online]. Available at: https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/623038 [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Arvidson M, Battye F, Salisbury D. The social return on investment in community befriending. Int J Public Sect Manag. 2014;27(3):225–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-03-2013-0045.

-

Barnardo's. 2012. The value of early on intervention. Identifying the social return of Barnardo's Children Center services. [Online]. Bachelor at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/the_value_of_early_intervention.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Chance T. 2013. Cambridgeshire's funded two-twelvemonth-former childcare social render on investment written report. [Online]. Bachelor at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/04/130624-SROI-Report-CCC-v4-Concluding-ane.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Lakhotia S. 2019. Incredible Years Parenting Programme. Forecast Social Render on Investment Analysis. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2019/05/Assured-SROI-Report-Incredible-years.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

New Economics Foundation. 2009a. The economic and social return of Action for Children'south Family Intervention Squad/5+ Project, Caerphilly. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/the_economic_and_social_return_of_action_for_children_s_family_intervention_team5_project_caerphilly.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019).

-

New Economics Foundation. 2009c. The economic and social return of Activeness for Children's East Dunbartonshire Family Service. [Online]. Bachelor at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/the_economic_and_social_return_of_action_for_childrens_east_dunbartonshire_family_service.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

New Economics Foundation. 2010. The economical and social return of Action for Children's Family Intervention Project, Northamptonshire. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/assurance%20submission%20final%20TVB.pdf [Accessed 13thursday Nov, 2019].

-

Action on Habit. 2014. SROI Analysis. A social return on investment assay of the K-PACT (Moving Parents And Children Together) Programme. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/AOA-SROI-M-PACT-2014.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Bradly J and Bolas C. 2013. Social return on investment (SROI) of Substance Misuse Work Leicestershire Youth Offending Service. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/SROI%20substance%20misuse%20Final%xx(1)%twenty(ane).pdf [Accessed 13thursday Nov, 2019].

-

Hackett C, Jung Y and Mulvale Yard. 2017. Pino River Institute: the social return on investment for a residential handling programme. [Online]. Bachelor at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/555e3952e4b025563eb1c538/t/595252a5d482e9a9a8d855c2/1498567338303/2017+SROI+small.pdf [Accessed xiiith Nov, 2019].

-

New Economics Foundation. 2009b. The economics and social render of Activity for Children'southward Wheatley Children'southward Center, Doncaster. [Online]. Available at: http://world wide web.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/the_economic_and_social_return_of_action_for_childrens_wheatley_childrens_centre_doncaster.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Winrow E and Tudor Edwards R. 2018. Social return on investment of Sistema Cymru-Codi'r To. [Online]. Available at: https://cheme.bangor.ac.great britain/documents/Codi%27r%20To%20(English)%20.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Bradly J. 2011. Social render on investment. Evaluation of the Leicestershire and Rutland Community Safer Sex activity Project. [Online]. Bachelor at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/CSSP_SROI_Evaluation_FINAL.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Children Our Ultimate Investment. 2010. Social return on investment. COUI. The Teen and Toddlers Plan. [Online]. Bachelor at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/Microsoft_Word_-_COUI_Teens.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Hoskisson A. 2012. Forecast social return on investment analysis. The Span Projection Western Australia. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/YMCA%20Bridge%20Project%20SROI%20Report%20v2%twenty(logos%20and%20assurance%20statement).pdf [Accessed xiiith November, 2019].

-

Butler W and Leathem K. 2014. A social render on investment evaluation of iii 'Sport for Social Change Network' programmes in London. [Online]. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5733282860b5e9509bc9c4db/t/573de713c2ea51d5e4d8e5c5/1463674646108/Active-Communities-Network-Social-Return-on-Investment-Written report.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Ward F, Thurston Thousand. RESPECT: A Personal Development Programme for Young People at Run a risk of Social Exclusion: Choice 1: Social Render on Investment. Chester: Academy of Chester Press; 2009.

-

Forth Sector Development. 2007. Restart. Social render on investment report. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/04/sroireport-Restart.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Goodspeed T. 2009. Workwise. Forecast of social return on investment of workwise activities (April 2009 to March 2010). [Online]. Available at: http://world wide web.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/04/SROI-Written report-Workwise-October-09.pdf [Accessed 13th November, 2019].

-

Leck C. 2011. Social return on investment (SROI) Evaluation Study, Baronial 2012 of the Houghton Project (October 2011 to September 2011). [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/Houghton%20Project%20SROI%20assured.pdf [Accessed 13th November, 2019].

-

NEF Consulting. 2017. Lancashire Wellbeing Service: Social return on investment. Executive summary. [Online]. Bachelor at: https://www.nefconsulting.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/LWS-Executive-summary.pdf. [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Gingerbread and New Economics Foundation. 2013. Getting together. The impact of local Gingerbread groups on single parent families in England and Wales. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/8468.pdf [Accessed 13th November, 2019].

-

Hoggett J, Ahmed Y, Frost E, Kimberlee R, McCartan Yard, Solle J and Bristol City Council. 2014. The troubled families programme: A process, bear upon and social return on investment analysis. [Online]. Available at: http://world wide web.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/04/A-Process-Bear on-and-SROIA-of-BCC-Troubled-Families-Plan.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Lukoseviciute L. 2010. Social return on investments in smoking cessation policy in the Netherlands. [Online]. Available at: http://arno.uvt.nl/prove.cgi?fid=113851 [Accessed 13th November, 2019].

-

Inge North. 2012. Social return on investment of Set for Work. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/06/socialreturn.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Bradly J, Butler West and Leathem K. 2013. A social return on investment (SROI) analysis of Double Impact citywide services in Nottingham for people recovering from alcohol/drug dependence. [Online]. Available at: https://www.doubleimpact.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/SROI_report_-_Double_Impact_Aug_2013.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Bosco A, Schneider J, Broome E. The social value of the arts for care home residents in England: a social return on investment (SROI) analysis of the imagine arts plan. Maturitas. 2019;124:fifteen–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.02.005.

-

Wellness Innovation Network. 2015. Peer back up for people with dementia. A social return on investment (SROI) study. [Online]. Available at: https://healthinnovationnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Social_Return_on_Investment_Study_Dementia_Peer_Support_Groups-one.pdf [Accessed 13th November, 2019].

-

House of Memories. 2014. An evaluation of House of Memories Dementia Preparation Programme: Midlands Model. [Online]. Available at: https://houseofmemories.co.uk/media/1011/business firm-of-memories-midlands-evaluation-2014.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Jones C, Windle G, Tudor ER. Dementia and imagination: a social return on investment analysis framework for art activities for people living with dementia. Gerontologist. 2018:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny147.

-

Social Value Lab. 2011. Craft Café. Artistic Solutions to Isolation and Loneliness. Social return on investment evaluation. [Online]. Bachelor at: http://www.socialvaluelab.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/CraftCafeSROI.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Stay Well at Dwelling. 2012. Stay Well at Dwelling house. Social render on investment (SROI) evaluation report – a summary. [Online]. Bachelor at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/ACK-SWaH-report-web1.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Jones K. 2012. The social value of a customs-based wellness project. Health Living Wessex. Social return on investment written report. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/04/HLW_Social_Value_Report_Revised-TVB-Sept12.pdf [Accessed 13th November, 2019].

-

Shipley R and Hamilton Fifty. 2011. Healthwise Hull. Social return on investment – forecast. [Online]. Available at: http://world wide web.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/SROI%20Report%20-%20Healthwise%20-%20February%202012%20revised%20FINAL.pdf [Accessed thirteenthursday November, 2019].

-

Chin C. 2016. Health Disability Sport Partnership: A social render on investment analysis. [Online]. Available at: https://whiasu.publichealthnetwork.cymru/files/6715/0210/7630/The_Health_Disability_Sport_Partnership_-_A_Social_Return_on_Investment_Analysis_FINAL.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Greenspace Scotland. 2013. Glasgow Health Walks. Social return on investment analysis. 1st April 2011 to 31st March 2012. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/Glasgow_Health_Walks_assured%20and%20formatted.pdf [Accessed 13th November, 2019].

-

Lobley N and Carrick M. 2011. Social render on investment evaluation report. Bums off Seats. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/BoS%20assured%20version.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Jones M, Pitt H, Oxford L, Orme J, Gray S, Salmon D, Meand R, Weitkamp E, Kimberlee R and Powell J. 2016. Food for Life. A social render on investment analysis of the locally commissioned program. Full report. [Online]. Bachelor at: https://www.foodforlife.org.uk/~/media/files/evaluation%20reports/4foodforlifelcssroifullreportv04.pdf [Accessed 13th November, 2019].

-

UK Government. 2012. Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012. [Online]. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.united kingdom/ukpga/2012/3/enacted [Accessed 12th November 2019].

-

Lang M. 2018. Why social value is and so important in the public sector. [Online]. Available at: https://www.supply2govtenders.co.uk/resources/web log/why-social-value-is-so-important-in-the-public-sector/ [Accessed 12thursday Nov, 2019].

-

Dynan K and Sheiner L. 2018. Gdp as a measure out of economic well-being. [Online]. Available at: https://world wide web.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/WP43-eight.23.18.pdf [Accessed 13th Nov, 2019].

-

Maier F, Schober C, Simsa R, Millner R. SROI every bit a method for evaluation inquiry: agreement merits and limitations. Voluntas. 2015;26(five):1805–30.

-

Burton-Jeangros C, Cullati South, Sacker A, Blane D. In: Burton-Jeangros C, Cullati S, Sacker A, et al., editors. xxx. Chapter 1 Introduction. A life class perspective on health trajectories and transitions. Cham: Springer; 2015.

-

Early Intervention Fund. 2014. Measuring the social impact of Early Intervention initiatives – A Guidance Document. [Online]. Available at: https://can-invest.org.united kingdom/uploads/editor/files/Invest/EIF/Guidance_on_measuring_the_social_impact_of_Early_Intervention_initiatives.pdf [Accessed 18th November, 2019].

-

Coast J. Assessing capability in economical evaluation: a life form arroyo? Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(6):779–84.

-

Fujiwara D. 2015. The seven principle problems of SROI. [Online]. Available at: http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/The%20Seven%20Principle%20Problems%20with%20SROI_Daniel%20Fujiwara.pdf [Accessed 12th Nov, 2019].

-

Jacobson PD, Neumann PJ. A framework to measure the value of public wellness services. Wellness Serv Res. 2009;44(v):1880–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01013.x.

Acknowledgements

Not applicative

Funding

Public Health Wales.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

KA designed the study, with input and guidance from PSB, TC, Doctor and MB. KA undertook the literature search, screening, extraction and collation of results. AS as well contributed to screening of the evidence. All authors edited and canonical the terminal manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Ethics approving and consent to participate

Not applicable. No ethical approving required for this systematic scoping review of existing evidence.

Consent for publication

Non applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher'south Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, as long as y'all give advisable credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party cloth in this commodity are included in the commodity's Artistic Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If cloth is not included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you lot volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zippo/i.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this commodity

Cite this commodity

Ashton, K., Schröder-Bäck, P., Clemens, T. et al. The social value of investing in public health beyond the life form: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health 20, 597 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08685-7

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08685-vii

Keywords

- Social value

- Public health

- Social render on investment, social cost-do good assay, life course

zunigathadisitud1984.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-08685-7

0 Response to "Return on Investment of Public Health Interventions a Systematic Review"

Post a Comment